Remoteness and severing threads to Polynesia

Pacific Ocean geopolitics, air travel and the chilenization of Rapa Nui

Remoteness: Time and geography.

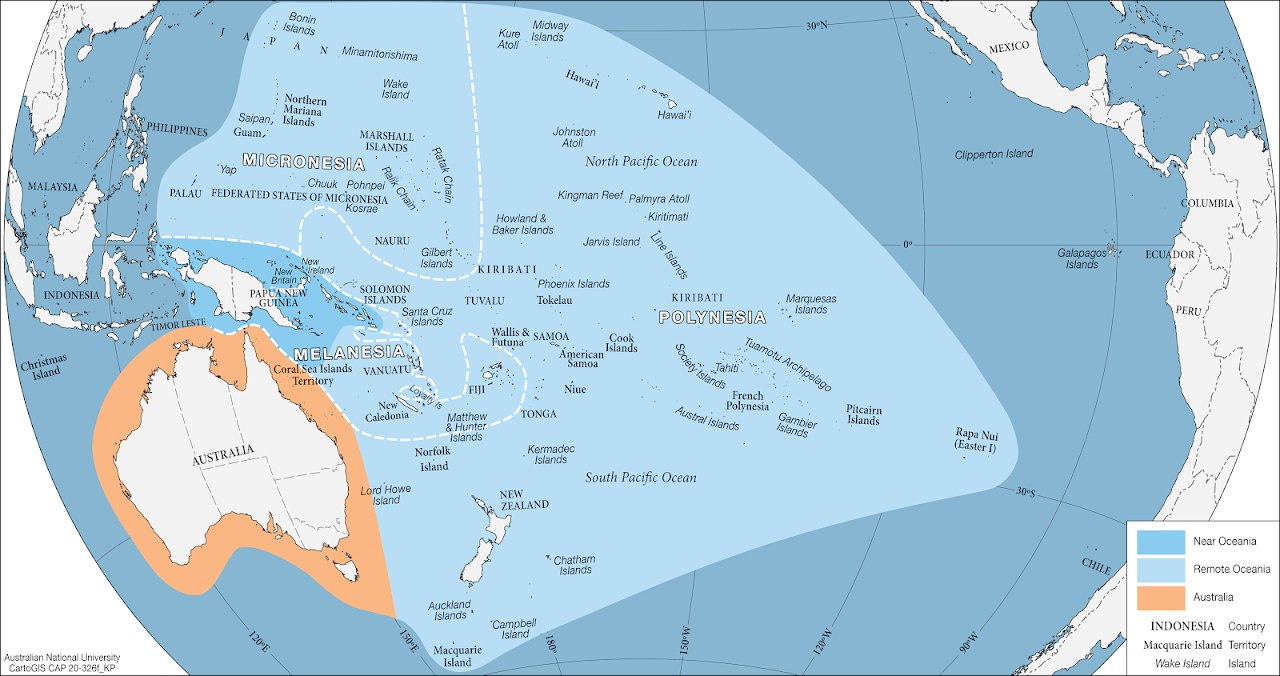

Remoteness should not be measured in kilometers or miles. It should be measured in time. A common trope about Rapa Nui is that it’s the most remote inhabited place in the world. Let’s analyze this in terms of absolute distance, in “geographical terms”. In ancient times, the now-called island of Henderson, part of the now-called Pitcairn group, was briefly settled by Polynesian explorers that decided to try their luck there for a few generations. At that time, this closest inhabited “neighbor” of Rapa Nui was 1921 km (1190 mi) to the west, until it was abandoned in the 14th Century AD. A substantial distance from a mere Polynesian “station” and this is the nearest Rapa Nui has ever been to other people if we can consider this close Polynesian kin as “others”. There are lands closer: Ducie Island, a small uninhabited atoll is 1558 km (968 mi) away and Motu Motiro Hiva (called Isla Sala y Gómez in official charts) is just 402 km (250 mi), an uninhabitable rock that serves as a bird colony, well known by the ancient Rapanui people.

Currently, the closest inhabited place to Rapa Nui is Pitcairn Island, the around 50 inhabitants of Adamstown living at a distance of 2073 km (1290 mi) west of Hanga Roa. This is the farthest distance today any inhabited place has from other people. Some like to claim that Tristan da Cunha in the South Atlantic, settled in the 19th Century, is more remote, being 2437 km (1514 mi) away from Saint Helena. However this usually omits that Gough Island, 400 km away has a meteorological station with about 6 personnel living there. So stay with me in considering Rapa Nui the most “geographically remote” inhabited place.

The fact that these distances are relative when trying to assess remoteness is immediately clear when looking at the times needed to cover them in the past and today. In ancient times, navigation to and from Rapa Nui must have taken weeks from and to anywhere else. Polynesian vessels that have replicated ancient navigation, like the Hokule’a from Hawaii and the Waka Tapu project from Aotearoa, took 16 or 17 days, from Mangareva in the Gambier Islands, about 2600 kilometers (1615 mi) away. Still, in the mid to late 19th Century, the French colonist Jean-Baptiste Onésime Dutrou-Bornier proudly mentions in a letter how it took him only 16 days from Valparaiso, in Chile (3668 km or 2279 mi away), breaking a new speed record. Air travel, that started in the 20th Century was a huge leap. The Manutara, a Catalina hydroplane took 18 hours from La Serena to Rapa Nui (3723 km or 2313 mi) in 1951. Today, a regular flight takes less than 5 hours from Santiago (3762 km or 2337 mi away) in LATAM’s 787-300 Dreamliners.

LATAM and Rapa Nui

So, far from the times of romantic land and sea exploration of the world, the world has become smaller. It no longer takes weeks from Polynesia or the Chilean coasts, or months from Europe or Asia, to get to Rapa Nui. The island is now only 4 to 5 hours away from Santiago. If we include average wait times at airports, it’s 9 hours away from Buenos Aires, 18 hours away from New York, 19 hours away from Los Angeles, 22 hours away from Madrid and less than a whole day from Paris. Of course this varies, but it shouldn’t change that much. Now, there is indeed a little catch here: LATAM is the only airline that offers a regular service to Rapa Nui since 1967 including its earlier names LAN Chile and LAN. The airline was stately owned when flights started and now its a private corporation, however it’s still the flagship Chilean airline and its of the utmost importance in communications within the country.

Before the COVID pandemic lockdown of the island in March 18 of 2020, LATAM offered daily flights from Santiago to Rapa Nui. During the high season it offered up to two flights a day from the Chilean capital. Since the island reopened to travelers, flights have been restricted for various reasons, including ongoing repairs at the single runway of the Mataveri International Airport in Hanga Roa. Currently, as of April of 2023, LATAM offers only 3 weekly flights, planning for daily flights to restart in October of this year. There is one thing missing, though.

Starting in 1967, all of LAN Chile’s weekly flights from Santiago to Rapa Nui flew another segment towards the Faa’a Airport in Pape’ete, Tahiti, and then back. It was a Santiago - Hanga Roa - Pape’ete - Hanga Roa - Santiago flight. This meant that Rapa Nui had one flight from Santiago, the political capital, and one flight from Tahiti, back from the cultural roots, near the Polynesian homeland. It was a symmetrical operation that the locals enjoyed. Some dozens of Rapanui (a community with only some 4000 descendants) live in Tahiti or in some other island of the Society Island’s group. Connecting with them was always a real possibility through the 5 hour long flight every thursday as a family visit, or for islanders simply wanting to go to French Polynesia, to explore the cultural ties to our fellow Pacific islanders was always within reach for any Rapanui.

At the turn of the century (and millennium), LAN Chile, from 2005 operating under its new moniker LAN, started to add more frequencies from Santiago, but reaching only as far as Hanga Roa and then flying back. The single weekly flight to Tahiti continued operating, but half a dozen flights just came from and went back to Santiago de Chile. It became an asymmetrical operation. The island’s demographics started to rapidly change as this time, with the local indigenous population becoming a minority around 2013 due to substantial inmigration from mainland Chile. Polynesian products, so conspicuous before: pearls, Hinano beer, Monoï coconut oil, French military style clothing, Pua’atoro canned meat, pāreu wraparounds and even French medicine started to wane in the shelves buried under tons of Chilean products. Some flowering plants, like the hibiscus that decorate mosts streets in Hanga Roa, came from there. Woodcarvers brought Mako’i (Thespesia populnea) wood, abundant in Tahiti, in order to protect the local Mako’i, very endangered since the 18th or 19th centuries. But this also became a lot more difficult due to regulations to bring these products enacted by the airline, now called LATAM, and the Chilean customs in the decade of the 2010s.

The Chilenization of Rapa Nui

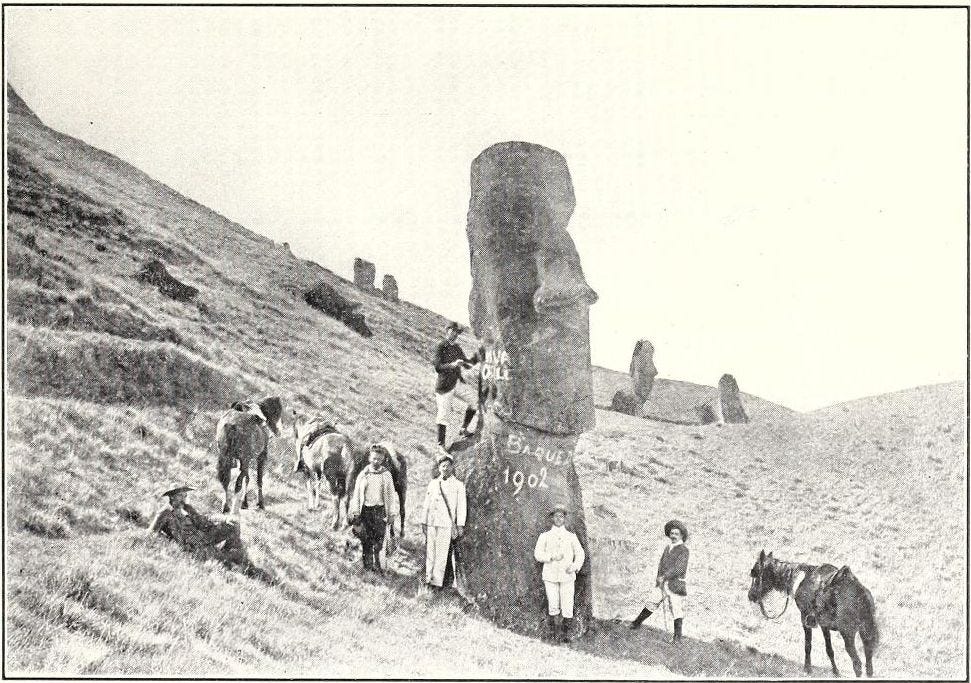

In 1888, in the late Age of Empire, several Rapanui chiefs and the representative of the Chilean State, captain Policarpo Toro Hurtado signed a treaty genearlly called “Acuerdo de Voluntades” by which the island would formally become part of Chile. Policarpo Toro had devised this plan to become, along with his brother Pedro Pablo, the owner of a sheep ranching business that earlier colonists had attempted without much success. By getting the Chilean government involved, he planned on using the state’s logistics and capabilities to maintain his “Company-island”, getting support and protection from this then growing naval power in the Pacific.

In those days, the Rapanui population on the island consisted in merely about 166 indigenous people (plus 12 foreigners). Rapa Nui had been ravaged by devastating epidemics since 1862: smallpox, flu, measles, tuberculosis, dysentery, etc. Losing hope in their homeland, hundreds of islanders left for Mangareva and Tahiti around 1871. Policarpo Toro had not much faith in their possibilities of survival in the long term. Those years saw the first (of two) predictions of the Rapanui people’s extinction. Toro hoped to lead a mass Chilean colonization of the island, gradually bringing more families to work in “his” island-wide estate, expecting the locals to either get finished by some other epidemic or assimilate to the colonizing families. A population replacement, like it happened in so many places in the Caribbean where the local populations were exterminated by disease, for example. A full-throttle chilenization of Rapa Nui.

His beliefs and plans fell short, though. The Rapanui stubbornly refused to disappear and the first group of families he brought could not adapt to the hostile conditions of living on the island, most leaving as soon as they could in the next ship. Also, Chile had greatly overestimated its capabilities of supplying regularly such a remote island, and the Chilean Civil War of 1891 completely destroyed any chance of Toro fulfilling his dream. For the next decades, Chile would use a private company as a proxy to establish its “rule” on Rapa Nui, but other than enforcing their colonial rules, the island remained essentially Polynesian: culturally, genetically and linguistically. For them, Chile was only an ominous presence that pulled strings from afar, and showed up once a year (if so) in the form of Navy ships. The ties with Polynesia remained strong in their worldview: from 1944 to 1958, at least eight groups of islanders attempted to escape the island in small boats adapted with sails. All of them went towards the west, towards Central Polynesia.

It was only in 1966 that the Rapanui would politically become part of Chile with the “Ley Pascua”. The reasons for this are multiple and complex, and we shall cover it elsewhere at a later time. Again, the process of chilenization was restarted. Hundreds of Chileans arrived to work at the different State institutions just brought to the island, and to work at the runway of the expected new airport. With air connection, remoteness was not as much of an issue as before, and the Chilean personnel and their families would stay. Suddenly, in the blink of an eye, Chileans became almost a third of the island’s total population of 1865 people. A second possible “extinction” of the Rapanui people was predicted: this time due to acculturation and assimilation when the indigenous inhabitants would finally embrace the “benefits” of becoming a Chilean. Again, this would also not happen. The chilenization process would take a lot longer than expected.

Conclusions

A few days ago, an article was published by La Depeche de Tahiti about the possibility of reopening the air connection between Hanga Roa and Pape’ete. After talks to executives from LATAM and Air Tahiti Nui, it was clear that there are no plans whatsoever of reestablishing this route. Even when the flights return to a normal pre-pandemic frequency, there are no intentions of connecting the islanders again back to their Polynesian brethren. The last umbilical cord to another destination in Te Moana Nui a Hiva was finally severed.

Is this part of the chilenization process, conscious or otherwise? LAN Chile, LAN or LATAM has never wanted nor allowed any other Chilean airline to get to their exclusive air route to Rapa Nui. And Air Tahiti Nui has a codeshare agreement with LATAM, in order to not compete with each other. It seems like the only way to make a trip to Rapa Nui from Tahiti profitable would be to continue towards Santiago and then back which is something that LATAM would certainly not allow. Up to March 2020, on any thursday, Tahiti was 5 hours away. If we would like to go to Tahiti now we would have to do:

Rapa Nui to Santiago: 4.5 hours

Santiago to Los Angeles: 11 hours

Los Angeles to Honolulu: 6 hours

Honolulu to Papeete: 6 hours

… not counting of course wait times at the airports and availability of flights. And not couting the hugely increased costs of such a round trip compared to the direct Rapa Nui to Papeete.

Papeete, Tahiti (4242 km or 2635 mi) is now incredibly far, incredibly remote for us, the Rapanui people. Our relatives there are very hard to reach. Timewise, they are much, much further away than people in Los Angeles (6864 km or 4265 mi). Even further away than our Polynesian brethren in Honolulu (7490 km or 4664 mi).

If the historical and geopolitical forces that aimed towards a chilenization of the island in one way or another are still operating in this postcolonial or neocolonial world (and trust me, at least some of them are), this is certainly a move in that direction.